Have I arrived or have I arrived? A surviving medieval vestige

Modern Catalan tends to use 'haber' for most compound tenses: "he comido," "he visto," "he llegado." But the islands, Alghero, and other parts of the Catalan domain retain 'ser' in expressions like "somos llegado" and "ha viene." Today, this system is receding, but it connects us with the history of the language.

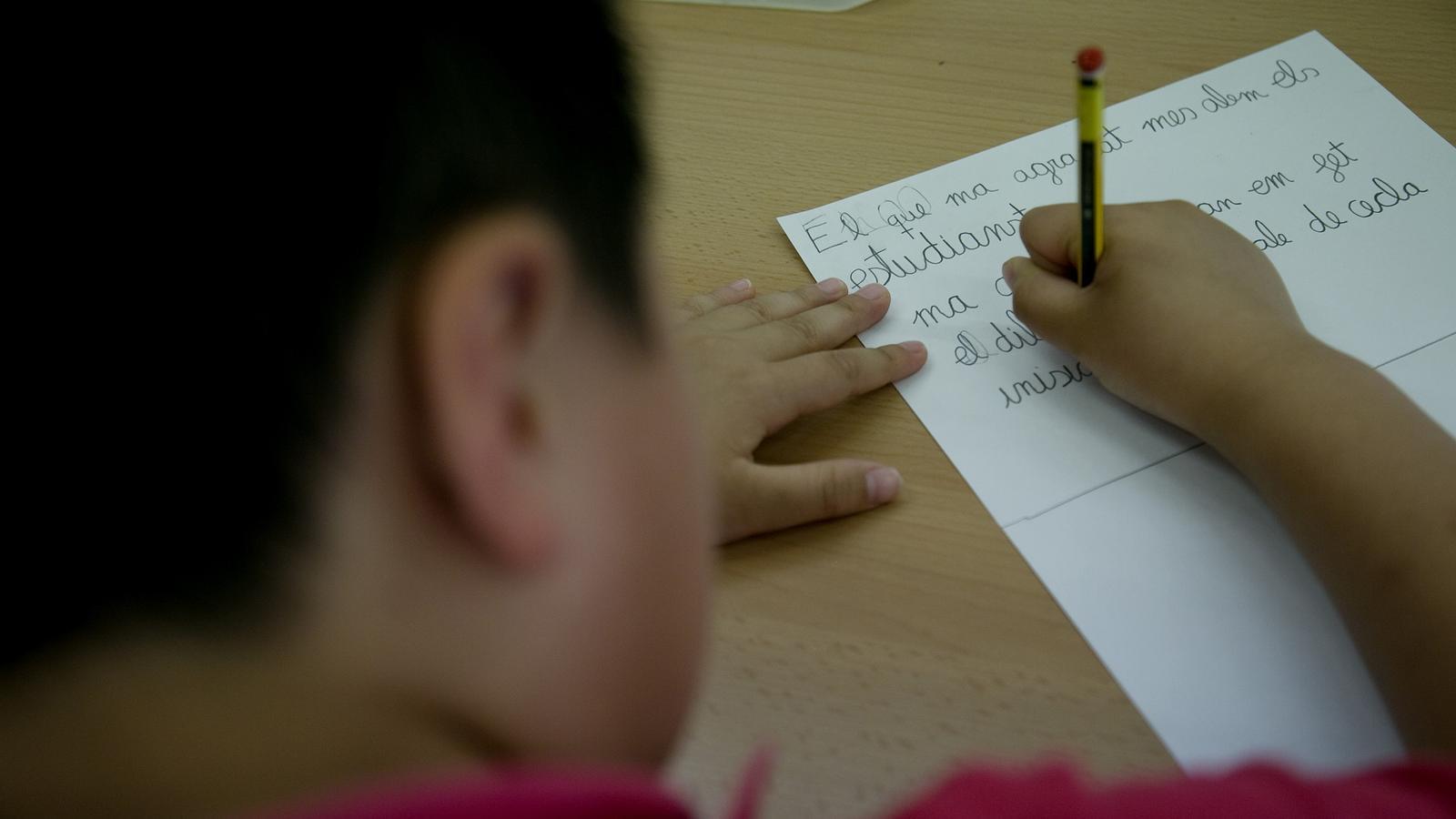

PalmWhen students return to school in September and write the typical "what I did this summer" questions, the answers are almost always the same: "I went to the beach," "I saw my friends," "I made my summer notebook." All with 'haber'. Now, anyone who has browsed through old texts or spoken with sponsors from certain places knows that things haven't always been so uniform. In many corners of the country, there are still people who, upon setting foot somewhere, explain that they've arrived, or that, upon seeing us, they're happy to have us back, with 'ser' instead of 'haber'.

In Old Catalan, compound tenses could be formed with 'haber' or 'ser', a choice that wasn't random. 'Haver' was used with transitive verbs, such as comer and ver, and with many active intransitive verbs, such as trabajar, risa, and repapiezar, among others. Instead, 'ser' appeared with verbs of movement and with verbs that described a change of state: "is come", "is departure", "were angry". Furthermore, when the auxiliary was 'ser', the participle agreed with the subject: "ellas son llegadas", "ellos son ido". This distinction responded to a clear logic: 'haber' indicated actions that the subject could control, while 'ser' 'se'.

'Ser' for 'haber'

Over time, the system was simplified. Most of the Catalan domain abandoned the use of 'ser' and remained with ''haber', as occurs in Spanish or Romanian. However, the change was not complete, which makes the case of our language especially interesting.

We travel, first of all, to Alghero. There, contact with Italian and Sardinian has helped to preserve the distinction, and it is still common to hear that our friends 'have arrived', that someone 'has died', or that, finally, our sleepy companion 'has gotten up'. The distinction depends on the verb and is similar to that of Old Catalan, so the auxiliary with 'ser' will tend to appear with verbs that indicate movement or change of state.

In Roussillon, the use of the auxiliary 'ser' is also preserved, but things are somewhat different, because the choice depends above all on the grammatical person. Thus, with the first and second persons (that is, ambjo and tú) 'ser' is used: "I have arrived", "you have been seen". In contrast, with the third person, the auxiliary is usually 'haber': "ha llegado" (ha arrived). It doesn't matter whether the verb is of movement or transitive: the key factor is who is speaking. This is a curious distribution within the Romance family, which shows how languages can reinvent their rules from similar starting points.

Ribagorzano offers yet another scenario. It seems to retain the use of 'ser in some tenses, but in reality it all comes from the formal coincidence between the forms of the two auxiliaries, 'haber' and 'ser', in some verbal tenses. Here, rather than continuity, what we have is a confusion of forms that has made it seem that the auxiliary is 'ser' when in reality it is no longer.

And in the Balearic Islands what we have is a mosaic. Currently the majority form is 'haber', but there are still those who say "somos llegado" or "ha viene", especially among older people or those from more 'rural' areas (if we can even speak in terms of rurality nowadays). In addition, there are hybrid cases that combine both systems. Thus, it is not unusual to hear ""I have arrived", with 'haver' as an auxiliary, but with the participle agreed with the subject (that, however, will be the subject of another article). These forms, which may be surprising to younger people (or speakers of other dialects), are evidence of a transition in progress. Languages such as French indicate that having two auxiliaries for the same verbal tense is not something exclusive to Catalan. In French, for example, a distinction is made. "je suis allé" (literally, "we are gone") of "j'ay mangé" ("I have eaten"), similar to the distinction that Italian makes between ""arrived dream" ("we have arrived") and "lo letto" ("I have read"). Outside the Romance sphere, German and Dutch differentiate "ich bin gigangen" either "ik ben gegaan" ("we are gone"), with 'to be', from "ich habe gesehen" either "ik heb gezien" ("I have seen"), with 'have'.

Two auxiliaries

On the other hand, Spanish, Romanian and Norwegian only have the auxiliary 'haber': "I have bequeathed", "together" and "jeg har kommet" ("I have arrived") are formed like "I have read", "am citit" and "jeg har lest" ("I have read"). We could say, then, that Catalan is halfway between the two-auxiliary system, which was the old one and is only preserved in some dialects, and the one with only one, which is the one used by most speakers today.

Although some might think that this is of no more interest than a dialectal curiosity, the reality is that these differences are very valuable for research: they allow us to understand how languages transform, how grammatical rules are reinterpreted, and how speakers can innovate within an inherited system.

In short, when we say that "we have been" somewhere and someone replies that it "has already been returned," what we have is a reminder that grammar is not a fossilized inheritance, but a playing field where tradition, innovation, and variation coexist. And, above all, these very specific details—how to choose between 'haber' and 'ser'—are precisely what allow us to better understand how languages are constructed and evolve.