My godmother is as much a 'pickme girl' as I am.

I don't hide it: since I was a child I have felt this urgency to be perceived and accepted by the male gaze, even finding a certain comfort in the unhealthy mold that was created for us in the image and likeness of the divas of the nineties and 2000s.

PalmThe other day I caught myself thinking, "I like that girl C. Tangana has now." Let's recap some facts about who he is: he also calls himself El Madrileño or Pucho, although his real name is Antón Álvarez. He is the author of songs as good as You stopped loving me and Laureating in the limo, among others, but also of a controversial photo on the deck of a yacht surrounded by women showing their backsides as if they were their trophies. Confusing the person and the character, it seems to me that he's playing at being a two-faced man, virile and tender, real and stupid: ironically (?) sexist. In short, C. Tangana embodies everything a guy should have to send you straight to a psychologist, as my friend Henry would say. And now it turns out he has a partner in whom, inexplicably, I find it easier to see myself.

She is Rocío Aguirre, a 36-year-old Chilean photographer, far from the media spotlight. Perhaps it is this last detail that makes me see her as a normal woman. Or perhaps because I think she is not like the rest of the girls in the famous yacht photograph. She is not Ester Expósito or Jessica Goicoechea, women who—unfairly, and despite themselves—are more famous for their looks than for their work (as if this depended on them and had any merit). She has conquered the man who sang "Bad woman, bad woman / Your icy nails have left scars all over my body"for her talent, for her way of being, not just for her good looks.

And why should this be any consolation? After going through all this mental journey, I saw how, another peak, I had fallen into the trap. I was looking for myself in the biblical division that separates women into saints and whores, the genesispickme girl': an internet-born term against machismo that has turned out to be quite misogynistic. According to Wikipedia, this concept refers to a woman who seeks male approval by rejecting feminine stereotypes and who wishes to be different from other women.

So there it was, mine. pickme girl interior, demanding validation. That the photographer had been the one chosen by the man of Too Many Women It made me be a little less hard on myself. I saw realistic standards, just the right amount of indulgence to make the level of demand I'm subjected to bearable, and for which they could take away my feminist card right now. I'm not hiding it: ever since I was little, I've felt this urge to be perceived and accepted by the male gaze, even finding a certain comfort in the unhealthy mold that was created for us in the image and likeness of the divas of the nineties and 2000s.

beauty of women' (1975), now collected in About women (Arcadia, 2025): "It's not the desire to be beautiful that's wrong, of course, but the obligation to be beautiful; or to try to be. What most women accept as a flattering idealization of their sex is a way of making them feel inferior to what they really are (...). Because the ideal of." Fifty years later, her words remain current and brilliant, helping me think more closely about ourselves, about ourselves and about that longing to be seen.

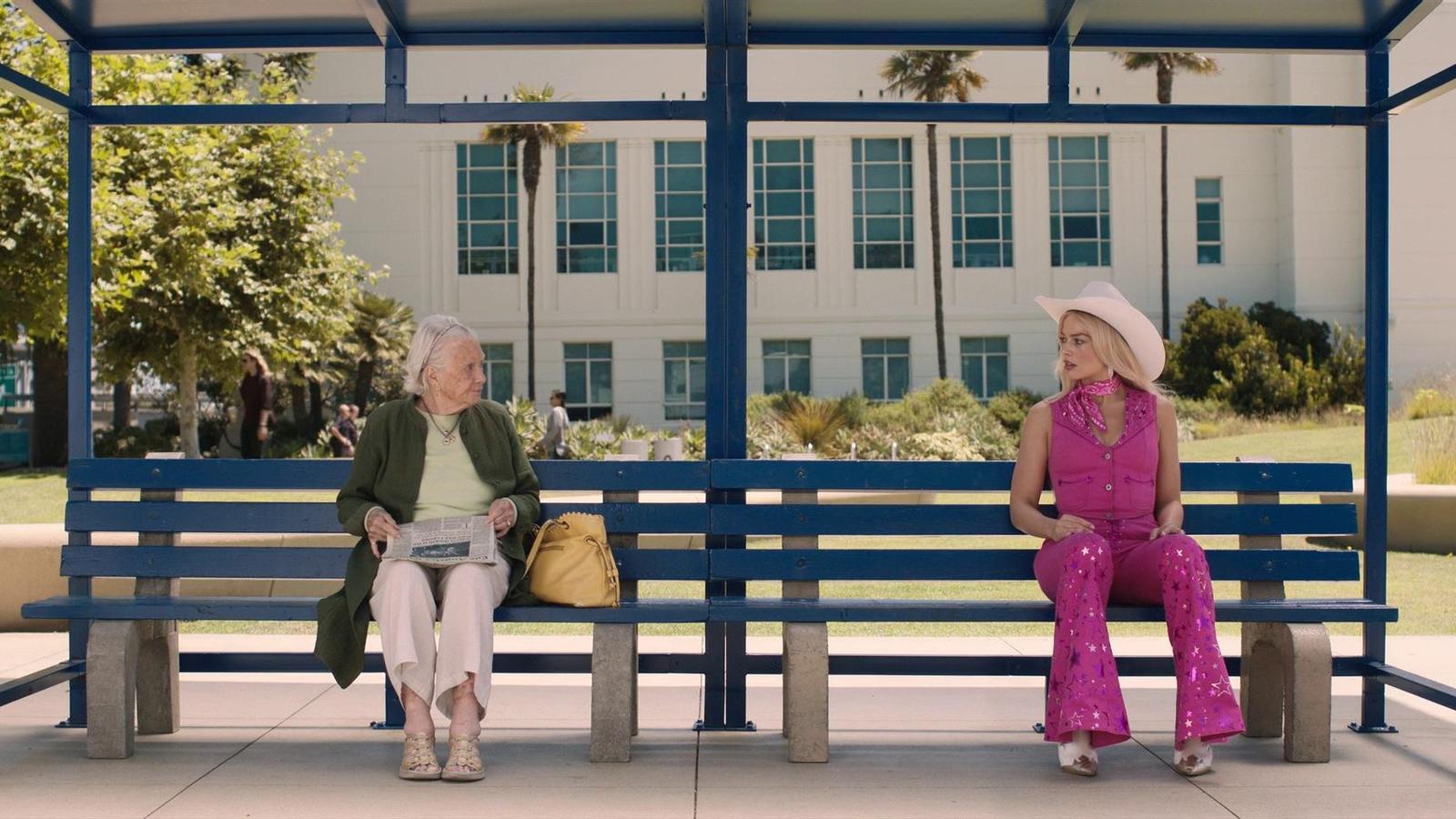

In one of the last conversations I had with my godmother, I wondered if that desire to be beautiful never rests. She, who was widowed by my grandfather more than 25 years ago, told me between the lines that a man she met at her day center threw flowers at her. She didn't say it clearly, but her attitude – visibly flattered – showed that this man, at 91 years old, still had the energy to celebrate with her. "He always tells me I come dressed up," she recounted with all the details that her post-war Galician stench allowed. It was as if that man's gaze validated her status, making her stand out from the rest of the women in the center, like a true pickme girl: "It's just that they all wear the same cardigan." Although she acted disinterested, she did attach importance to some of the man's gestures—"tall and cultured," she insisted—as if he had asked for her one day when he was absent. "I didn't even know his name," she added, powerfully.

"Beauty is undoubtedly a form of power," Sontag continues in the aforementioned article. "The sad thing is that it is the only form of power most women are encouraged to achieve. This power is always conceived in relation to men; it is not the power to do, but the power to attract. It is a power that denies itself," she concludes. It's a shame that Sontag didn't get it to my godmother in time either.