The Mallorcan who exported organic gardens to the world

Gaspar Caballero de Segovia, a musician from Petra who became a pioneer of organic farming, devised a sustainable farming system that has reached schools, farms, and restaurants around the world.

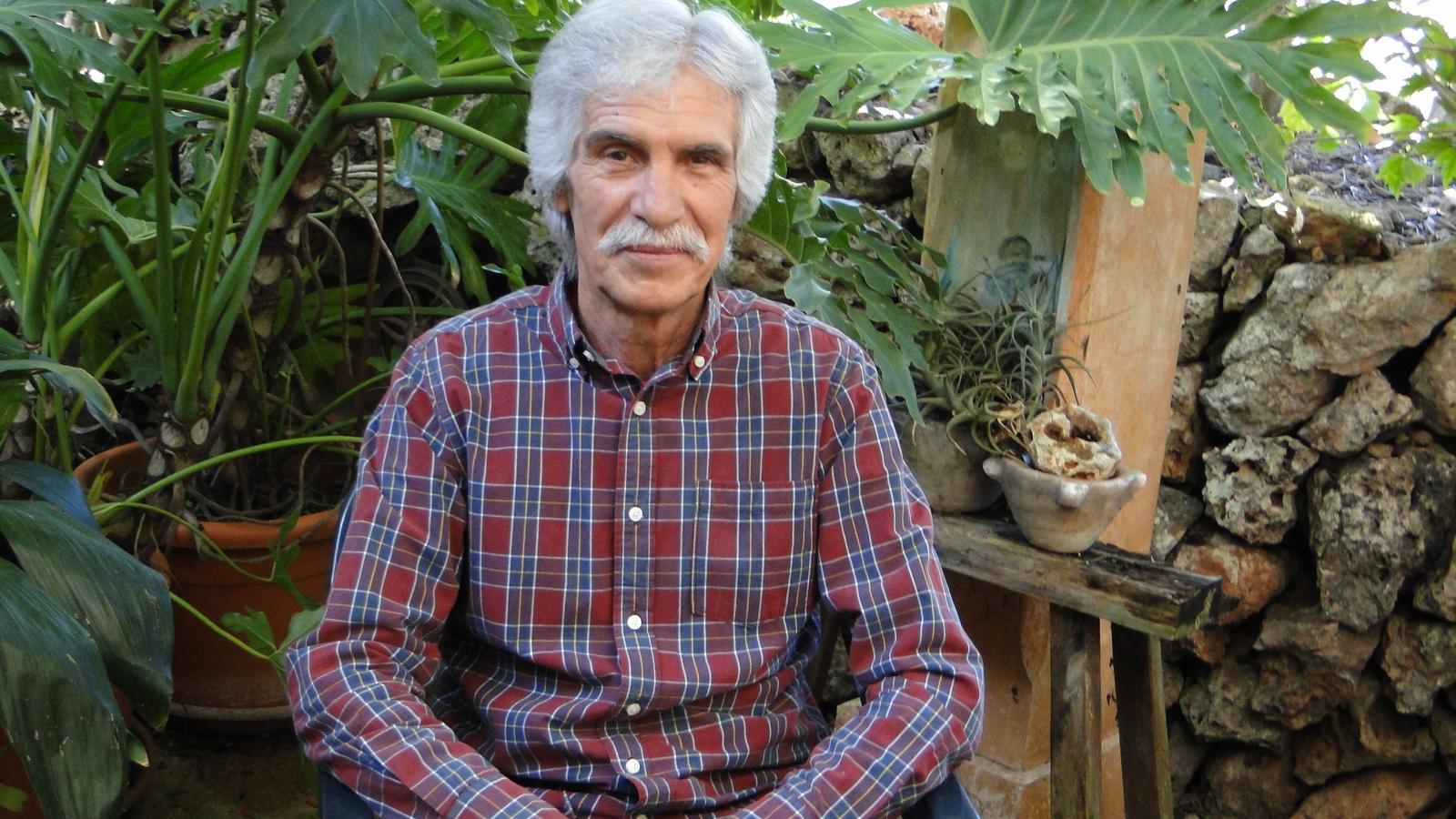

PalmGaspar Caballero de Segovia Sánchez (Petra, 1946-2024) didn't work in the fields, but rather in music—he was a bassist and moved around Ibiza during the height of hippie culture. But for health reasons, he became interested in organic farming. And what began as a personal commitment became a revolution that has transformed the way hundreds of people farm. His farming method, known as crestall stops, has been replicated in schools, foundations, restaurants, and private gardens in several countries around the world. And it all began on a small farm in Costitx.

In the early 1980s, Caballero began experimenting on his farm, Sa Feixeta. "It was called that because it was like a narrow strip," Joan Coll, a close friend of Caballero and his disciple, explains to ARA Baleares. Caballero's goal was to find a simple, efficient, and respectful way to create a vegetable garden that didn't depend on chemicals and maximized the soil's fertility. In 1991, he gave his first public presentation of the method at a course organized by the Union of Pagesos of Mallorca.

Over time, this set of techniques was systematized into his own method, which he eventually called the Gaspar Caballero de Segovia Method, adapted to the Mediterranean climate and eschewing conventional agriculture and its excesses. "His approach was so strong that he didn't even sprinkle sulfur on the soil, even though it's allowed to a certain extent," says Coll.

What are the stops in Crestall?

The method is based on paradas: rectangles of earth 1.5 meters wide and up to six meters long, covered with a layer of organic compost (called crestall). This compost, also known as balsa manure, is obtained from plant remains and manure, and is not mixed with the soil. It acts as a protective cover that retains moisture, prevents erosion, and nourishes the soil. "It imitates the layer of tin that creates humus in forests," explains Andrea Landeira, a biologist and environmental educator at the Mediterranean Wildlife Foundation, who, like Coll, also continues Caballero's legacy.

One of the basic principles is to never step on the cultivated soil, so as not to compact it. Therefore, the stalls are surrounded by walkways made of ceramic slabs that allow access to the garden without damaging it.

The planting is denser than traditional horticulture dictates: the plants are closer together, the leaves touch, creating a microclimate that reduces evaporation, prevents weed growth, and promotes moisture retention.

Between the stalls, herbs and flowers are planted, serving a dual purpose: attracting pollinators and repelling pests. Caballero also added an exudation irrigation system—a fabric tube that releases water evenly—and crop rotation by botanical family, which maintains soil fertility and prevents the spread of disease.

A method born in Mallorca and spread throughout the world.

"No one is a prophet in their own land," says Joan Coll. Despite being Mallorcan, Caballero's success was greater outside of Mallorca than within. He brought his system to many schools in the Basque Country, "up to 60 centers," says Coll. He also developed educational projects in different parts of the Canary Islands and provided training in Cuba, at Schumacher College in England, and even as far as Africa. He even carried out projects with the Miró Foundations, both in Palma and Barcelona.

Joan, who is also an environmental activist and the owner of the Es Ginebró restaurant in Inca, met Gaspar more than 30 years ago. "I never took a course, and he would tell me: 'This guy, who's never taken a course, does the parades better than me.' But my trick was that I could call the maestro whenever I had questions; I had the maestro online, even though there was no internet back then," he says with a laugh. "I ended up with 28 parades, all following his method," he recalls. "He was a true professional," he sums up.

Biologist Andrea Landeira explains that the method's success lies in the fact that "it's a system that reproduces the natural conditions of the forest: a cover of organic matter that protects, nourishes, and maintains moisture. Although common now, it was something very new when he first started using it." According to Landeira, the system stands out for its simplicity and use of local compost.

Caballero's Legacy

Gaspar Caballero died in 2024 after battling cancer in recent years. Both his daughter, Sabina Caballero de Segovia Amengual, and his widow, Celsa Amengual Mariano, agree that the recognition of his method in Mallorca was not easy. "He was saddened because where he was born, they didn't give him importance, he wasn't recognized despite the method having been successfully replicated in many parts of the world," explains Celsa.

His daughter, who keeps his legacy alive and continues to take courses and spread her father's work, points out that Gaspar was a pioneer, although at the time he was considered the town's madman. She emphasizes that the method is very simple and easy to start and that it even has "a therapeutic aspect for older people accustomed to living in the countryside, as it can be adapted for wheelchair users."

Sabina also remembers Tomás Martínez, who was Gaspar's comrade in struggle "for organic horticulture," and "particularly" highlights his work in bringing organic school gardens to schools using her father's method. "They were two visionaries who were 25 years ahead of their time; I'm sure they're both making a killing wherever they are," she says.

Despite the obstacles and initial lack of recognition, Gaspar's legacy is more alive than ever. His teachings continue to circulate among groups of farmers and educators. And his method continues to be implemented in schools, urban terraces, farms, orchards, and family gardens. "Believe in what you do," that was the key, Joan explains. "And he truly believed. He was very ecologically conscious. He loved the land, respected it, and taught others to do the same... that was his philosophy," she concludes.