Poems in Spinoza

Borges completes the biographical profile of the philosopher by making it known that he loves solitude and that he is not attracted to either fame or love.

Jorge Luis Borges shows his admiration for Spinoza's philosophy, dedicating two complete poems to him, entitled 'Spinoza'. The first is included in the collection The Other, the Same (1964), and the second in The Iron Coin (1976).

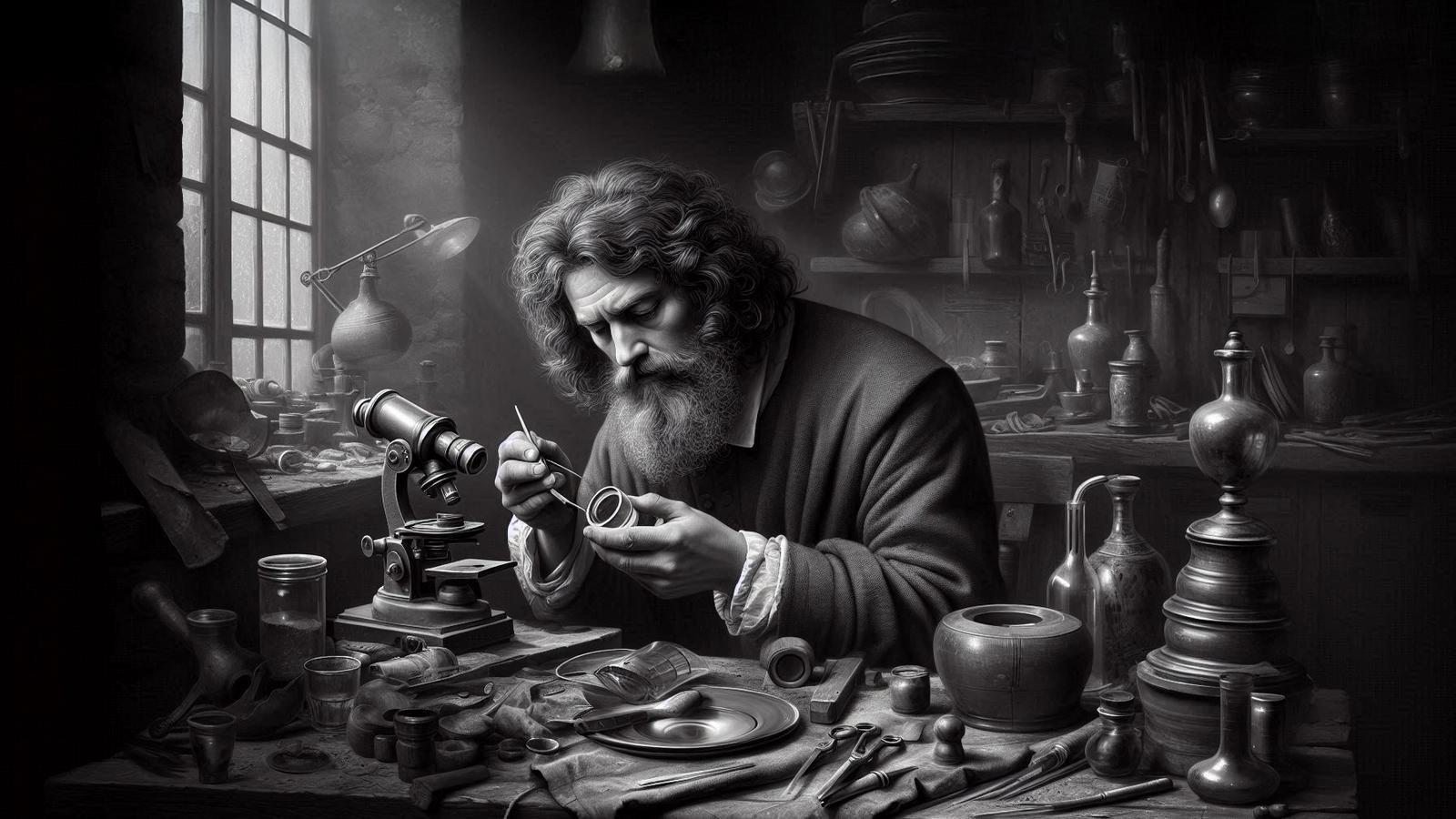

In the first poem, Borges imagines Spinoza on an ordinary winter day, working in his workshop in the twilight, at dusk. He refers to the philosopher's manual trade as a polisher of high-precision glass lenses destined to be part of optical instruments, such as microscopes and telescopes. This is a trade that allowed him to establish ties with prominent members of the European scientific community such as Christiaan Huygens and Robert Boyle, in a context marked by the scientific revolution, and which provided him with enough income to live and dedicate himself to philosophy.

At the beginning of the poem, he alludes to the philosopher's "translucent hands" with the intention of showing that by making transparent lenses he lets the light of truth pass through. And in passing, we can think that in the hands that are lenses there is no exploitation, nor alienation, nor strangely, only the effort of a craftsman who supports the craftsman who supports. He then adds that these hands belong to a Jew who lives in the "ghetto." We know that he is referring to the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam, where the philosopher lived with his family until the hero or excommunication and expulsion from the Jewish community, accused of atheism, specifically, of denying the immortality of the soul and affirming that God is nature. The religious punishment is a civil death that severely conditions Spinoza's life and treats him as an outcast, through the prohibition of giving him work, and the obligation to avoid personal contact, verbal or written, not to give him food or lodging, or to help him in any other way. Although it is not true that Spinoza worked as a lens grinder within the ghetto. In this, Borges anticipates reality, since he begins to do so later, after being expelled, at the age of twenty-three.

From Manual to Intellectual Labor

Borges implies that Spinoza forgets his hands and his confinement in the ghetto, and that he dreams of "a clear labyrinth," that is, a way out, which could be a dedication to philosophy. However, this subtle shift from manual to intellectual labor allows us to remember that Spinoza combined both activities to the point of being inseparable and carried them out wherever he lived in the Netherlands. According to the interpretation of the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, Spinoza's geometric method that gives rise toEthics demonstrated according to the geometric order, known simply as Ethics, is a consequence of the thoroughness, precision, concentration, and search for clarity that he applies to his craft. Deleuze speaks of an optical geometry that runs through the work, and that must understand Spinoza holistically, as a philosopher-craftsman.

Borges completes the biographical profile of the philosopher by making it known that he loves solitude and is not attracted to either fame or love. And he ends the poem with a note that defines his philosophy as rationalist, "free from metaphor and myth," and speaks of the most precious discovery, that of infinity, represented by the figure of God who guides the gaze through the crystal toward the universe.

In the second poem dedicated to Spinoza, Borges describes him as a Jew "with sad eyes and citrine skin," already advanced in age, like "a leaf that declines in the river," sick, close to nothingness, but who persists in the task begun in his youth of "polishing." Borges focuses on the philosopher's relationship with God through his Ethics, thus giving thematic continuity to the previous poem, beginning where the other left off.

Spinoza is seen by Borges as a creator of the infinite, a man who "constructs God in the shadows" and demonstrates his existence geometrically, "with the word," applying a meticulous and systematic method based on the connections between definitions and explanations, axioms, demonstrations and propositions, prefaces and appendices, advancing his arguments stimulated by a love for God that expects no reciprocity nor to be rewarded, an intellectual love which, in Spinozian terms, must occupy "the mind to the maximum," because he who knows himself and things best, knows God best and is wiser, inseparable from the divine substance.

Borges also quotes Spinoza in at least five other poems. Chronologically, he is cited as "the geometric Spinoza" in the poem entitled 'The Alchemist', in which he presents his pantheistic vision of an eternal god who "is everything," the alternative to the being that is water of Thales of Miletus. In the poem entitled 'Israel', he speaks of his Jewish condition, which links him to the fate of many other hated and persecuted men. He also makes a brief mention of another poem, this one dedicated to G.A. Bürger, an 18th-century German poet who knew that "we are made of forgetting," which in Borges's eyes made him wiser, but does not change the fact that existence is marked by forgetting, as is knowing the corollaries.Ethics Spinoza's theory also does not prevent the passage of time and its effects. In the poem 'Nihon' (Japan or 'Land of the Rising Sun'), he mentions Spinoza's infinite substance and its equally infinite attributes, including space and time. This is a truth deduced from the definitions, axioms, propositions and corollaries that structure the poem.EthicsFinally, in the poem 'Someone Dreams', he compares the poet Walt Whitman to Spinoza's divinity, because, like him, he chooses to "be all men."

Dispense with desires

Ponç Pons, a poet from Alaior and enthusiastic about Spinoza, lives philosophically in Menorca. He declares his willingness to follow his lessons and simple lifestyle, forgoing certain desires and renouncing "riches, honors, pleasures, and vanities" to be happy. He discusses all this and more in his collection of poems. The blue trail of ants (Cuadernos Crema, 2014), through aphorisms filled with Spinoza's beauty and truth. In one of his first thoughts, he confesses that he tries to polish his words, as if they were slow, "to be able to see the world more clearly through them." He acknowledges, after a hard afternoon of work, that he regains his strength by reading Spinoza and listening to country music. At another point, he rereads Spinoza, recalls the excommunication he suffered, and reflects on how power uses fear as an instrument of corruption. He complains about the lack of interest Spinoza arouses in cultural supplements, which are focused only on the new postmodern thinkers. He sarcastically refers to the degraded state of Nature, which is God, and in the same tone, reflects on the astonishment of a gardener who does not challenge Spinoza's conception of "all is God," and who also believes that it cost him too much to create the world. He speaks again of God as an omnipresent divinity: "In word, in deed, in the open air...", and above all, outside of temples. And he shares Spinoza's defense of human freedom, with the nuance that being free is equivalent to acting according to the needs of nature, while criticizing Spinoza for accepting all ideas referring to God as true, and for failing to perceive them with an intolerant and repressive attitude. Finally, he is shocked by Spinoza's premature death, at just forty-four years old. Most likely, he was killed by the crystal dust that accumulated daily in his lungs due to his work.